There are a wide variety of guidelines and recommendations in the world of passenger and light truck tire service. As someone who is partially responsible for establishing those guidelines and recommendations, the challenge is to determine the degree of care that must be followed.

In some instances, the guideline is communicated as a “must” or “always.” In order for something to be a “must” or “always,” there has to be a direct correlation between safety and the failure to follow the guideline. For example, when it comes to tire repair, the tire must be removed from the rim so the interior can be inspected. Failing to remove the tire from the rim as part of the tire repair process may result in a significant safety risk to the driver if the damage on the inside is severe. Therefore, demounting the tire from the rim is a “must” in the world of tire repair.

On the other end of the spectrum, “never” reflects a guideline where the consequences are severe and safety is impacted directly. To use the tire repair example again, the industry unanimously agrees that tires should never be repaired on the rim.

Another example can be found in the “Care and Service of Passenger and Light Truck Tires,” published by the Rubber Manufacturers Association (RMA). According to the RMA, technicians should “Never ‘bleed’ or reduce inflation pressure when tires are hot from driving, as it is normal for pressures to increase above recommended cold pressures.” Again, the consequence of deflating a hot tire is often underinflation or overloading, so the RMA has made it a “never.”

The tire and wheel business has its share of guidelines that are a “must, always, or never,” but there are also some that are “should” or “recommended.” In those instances, failing to follow the guideline can have negative effects, but the risk to safety is not as direct or severe. From the legal perspective, there is enough gray area for someone to make a good argument that there are exceptions to the rule or there isn’t unanimous consent among industry experts and authorities.

In the world of custom tires and wheels, there are a lot of different ways that installers can end up in court. When it happens, the plaintiffs will focus on whatever guideline or recommendation was not followed that violated the standard of care and caused the accident. Based on my 20 years as an educator and 10-plus years as an expert witness in court cases, here is my personal opinion on how tire retailers can protect themselves from liability (but you’re still going to get sued and end up in court).

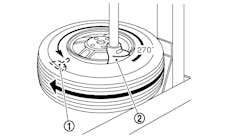

1. Follow the 3% rule.

Since the goal of most custom tire and wheel packages is to switch from the original equipment size to a larger tire, the best place to start is the 3% rule. Years ago, several tire manufacturers recommended that plus-size fitments remain within 3% of the diameter of the OE tire specified on the placard. Since then, very few, if any, have continued to publish that guideline, but it still exists in the Tire Industry Association’s (TIA) Automotive Tire Service (ATS) Program and will remain there because it has been used in a number of legal cases. There have also been a number of tests in the past that showed exceeding the 3% guideline can have a negative effect on vehicle stability, electronic stability control, and other ride or braking systems.

In order to illustrate how it works, let’s look at a real world example. The 2014 Cadillac Escalade has an OE tire fitment of P265/65R18 112S. According to the Tire and Rim Association (TRA) Annual Yearbook, the P265/65R18 has an outside diameter of 31.54 inches. Since the 3% rule is a plus/minus, the retailer just needs to perform simple math to get the range of acceptable diameters: 31.54 x .97 = 30.59 and 31.54 x 1.03 = 32.49. This means that sizes other than the OE fitment should have an outside diameter between 30.59 and 32.49 inches. The other factor that needs to be considered is the load index. The OE tire has a load index of 112, so the replacement tire must have a load index that is equal to or higher than 112. This isn’t a “should” or a recommendation. Retailers can never install a replacement tire with less load carrying capacity than the OE specification.

According to the RMA, “Replacement tires should be the same as the OE size designation, or approved options, as recommended by the vehicle or tire manufacturer.” Since the 3% rule comes from the tire manufacturers and the guideline itself is a “should,” plus-sizing is allowed as long as certain restrictions are followed.

A few years ago, I was involved in a legal case where the custom tire was .12 inches over the 3% threshold for the original equipment tire. That was more than enough for the plaintiff to suggest it was not compliant with industry guidelines. Never mind the fact that a tenth of an inch in diameter amounts to a few millimeters difference in ride height. I was representing the wholesaler who sold the tires to the retailer and maintained that the installer was ultimately responsible for fitment decisions. It didn’t matter because the installer had virtually no insurance, so the plaintiff went after the wholesaler who had a policy with a much higher umbrella.

Installing tires with diameters outside the 3% limit is going to come with a higher degree of risk. It’s been out there long enough that dealers should know about it and, therefore, follow it at all times. There’s always going to be the customer who wants to push the limits of plus sizing, so the retailers who are focused on those types of sales just need to know that they come with increased risk.

2. Do not downgrade the speed rating if it is listed on the placard.

There is some controversy about speed ratings for a variety of reasons. The most obvious is the fact that speed limits in North America prohibit anything even close to the maximum speed for the tire. That’s why I’ve always described them as “performance ratings” because they say more about the degree of performance than the speed. The issue at hand is the following RMA guideline:

Speed rating must be equal to or greater than what is specified by the vehicle manufacturer if the speed capability of the vehicle is to be maintained.

If that statement seems contradictory, then it will be easier to understand how speed ratings relate to potential legal action. The manufacturers provide enough “gray” for the dealer to install a tire with a speed rating that differs from the specification on the placard, so they include a disclaimer that says the speed capability is reduced.

Individual manufacturers will warn about handling differences when lower speed ratings are selected and everyone still agrees that the best practice for selecting replacement tires is to use the exact OE size, load index and speed rating.

If the goal is to avoid a lawsuit, then retailers should never downgrade the speed rating. There are just too many disclaimers, warnings and cautionary statements against reducing the speed rating if one is listed on the placard.

On the other hand, if the placard does not indicate a speed rating, then it shouldn’t be an issue.

Just remember, if the OE fitment on the placard includes a speed rating, the maximum speed of the replacement tire must be equal to or greater than the speed rating listed.

If it isn’t and the vehicle is involved in an accident that results from the loss of control, the plaintiff will certainly point to the lower speed rating as a contributing cause. Why take a chance?

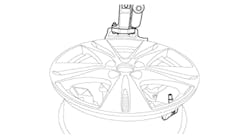

3. Make sure the wheel is compatible with the vehicle.

Custom wheel manufacturers publish fitment guides, and they are the authority when it comes to selecting the proper wheel for a vehicle. Installers must look beyond things like bolt circle and hub bore diameter to make sure there are no additional factors that can lead to a problem.

In other words, just because the bolt pattern is identical and the wheel appears to fit the hub it doesn’t mean the fitment is correct.

Years ago I was involved in a case where a dealer rotated a set of custom wheels and shortly after the rotation, one of the wheels became loose and caused an accident. The plaintiff discovered that the wheels in question were not approved for the vehicle, so a different retailer did not follow the manufacturer’s recommendations at installation.

Like the 3% case and the wholesaler, the installing dealer did not have much in terms of insurance but the retailer that rotated the tires was a large company. It was a classic case of the “deep pockets theory” and once again, the insurance company eventually settled.

The legal principle known as “Standard of Care” basically determines what the reasonable expectations would be in a given scenario. In no way do I think it’s reasonable for a dealer to check and see if a custom wheel fitment made by someone else followed the manufacturer’s fitment guidelines.

There has to be some degree of common sense in these situations because there are literally hundreds of different custom wheel options, and no one could be expected to even maintain a library of every wheel on the market.

However, the retailer who sells and installs the custom wheels is held to a much higher standard, so every fitment decision must be consistent with the guidelines and recommendations established by the wheel manufacturer — without exception.

4. Make sure a wheel torque program is in place.

Years ago, TIA introduced RIST to help tire dealers understand the necessary components of a quality wheel torque program. The “R” stands for remove debris from mating surfaces, the “I” stands for inspect components, the “S” stands for snug the nuts in the star pattern, and the “T” stands for apply the recommended torque.

For years, the industry preached the importance of torque without addressing the factors that translate into clamping force. As a result, companies that switched to torque control devices like torque wrenches immediately saw the number of loose wheels and related problems go up. I’ve always said torque is the setting on the oven because it is a measure of force like temperature is a measure of heat. And just like a recipe, if the ingredients are wrong or the directions are not followed, the correct temperature of the oven means absolutely nothing.

On custom wheels, the “Remove” step is critical, especially when the hub bore in the wheel does not have a bevel or recess where it meets the concentric ring on the hub. If there is debris between the mating surface of the wheel and the hub or drum, the correct torque at installation will not be correct for long once the debris works its way out. Also known as “joint settling,” the natural flexing of the wheels in service results in the loss of clamping force when the mating surfaces are not clean.

The “Inspect” step of RIST should be obvious because worn or damaged components are not going to contribute to wheels staying on the vehicle, with or without the correct torque. It’s equally important to inspect the bolt holes for any damage or wear, and if a hub-centric ring is used, it too should be inspected.

“Snug” is fairly basic, but it should always be done in a star pattern to ensure the seating process is equal around the hub.

“Torque” is the final, and most difficult, step in the RIST procedure. The best practice is to use a torque wrench set to the specification for the OE wheel. Technicians should tighten each nut to the recommended torque in a star pattern and avoid applying force after the wrench “clicks.”

Torque wrenches should be handled with care, periodically calibrated, and stored at the lowest setting so the tension on the spring mechanism is not compromised. Torque limited extensions, or torque sticks, are faster, easier and cheaper, but they are not as consistent and rely heavily on the impact wrench, the compressed air system and the technician. If torque limited extensions are used, then they must be regularly checked against a calibrated torque wrench.

I also recommend documenting torque checks so you can prove there is a quality control system in place to verify the torque sticks are accurate.

The most important factor is to have a torque program that incorporates the RIST procedure so every technician installs wheels the same way all the time. They should know what to look for and have all of the tools and equipment to do the job properly.

It’s also a good idea to advise customers to return for a torque check after the first five to 50 miles to check for any settling or torque loss. Failure to warn is a lay-up for the plaintiff when it isn’t on the invoice or addressed at the time of sale.

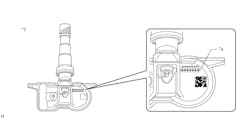

5. Make sure an operational TPMS is operating after tires and/or custom wheels are installed.

According to the make inoperative provision of 49 USC 30122(b), manufacturers, distributors, dealers or motor vehicle repair businesses are prohibited from knowingly making inoperative, in whole or in part, any part of a device or element of design installed on or in a motor vehicle in compliance with an applicable motor vehicle safety standard. That statement was interpreted in countless different ways for years, so TIA asked the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) to address the issue.

TIA: If a motorist purchases a set of aftermarket wheels and declines to purchase new TPMS sensors, does the service provider violate the make inoperative provision in 49 USC 30122(b)?

NHTSA: If the vehicle has a functioning TPMS system at the time he or she purchases aftermarket tires and wheels, the service provider would violate the make inoperative provision by installing new tires and wheels that do not have a functioning TPMS system.

In some ways, this is a perfect example of asking a question only when you are prepared for an answer. Common sense would say that if a customer refuses to purchase sensors with tires or wheels, the installer can’t force them to spend the money if they understand the risk and choose to drive around with the TPMS light on all the time.

NHTSA’s response says otherwise. If the TPMS is working with the old wheels when a vehicle arrives, then it must be working after the new wheels are installed. However, if the system isn’t working when the vehicle arrives, then it isn’t operative, which raised another question and answer exchange between TIA and NHTSA that went something like this:

TIA: If a motorist is made aware of an inoperative TPMS sensor and declines to purchase a new one, can the service provider remove the dead or damaged sensor and replace it with a rubber valve?

NHTSA: A motor vehicle repair business would not be violating 49 USC 30122(b) by removing an inoperative or damaged TPMS sensor and replacing it with a standard snap-in rubber valve stem.... However, if the malfunction indicator is disabled, a violation would occur.

According to this answer, the installer cannot force the customer to make the TPMS system operative. In other words, an inoperative system cannot be made inoperative. Ultimately, the rule regarding TPMS for custom tires and wheels is quite simple. If the TPMS is operating when the vehicle comes in, then it must be operating when it leaves. If the TPMS is not operating when the vehicle comes in, then it can remain inoperative when it leaves, with one caveat: The service provider cannot disable the malfunction indicator light on the dashboard.

Given the black and white nature of this issue, it would be advisable to document an inoperative system at the time of installation so there are no questions.

I am not an attorney, and none of this should be considered legal advice. In fact, I recommend that you take this to your legal counsel and your insurance company and go over each point so they can advise you on what you should or should not do.

That being said, I’m still confident that if retailers follow these five suggestions, then their liability will be reduced.

There is no way you can avoid a lawsuit if there is an accident and you get caught in the wake of an aggressive plaintiff’s attorney. All you can do is protect yourself from becoming an easy target by following the industry guidelines and recommendations as often as possible. ■

See two more ways to avoid lawsuits by clicking here.

Kevin Rohlwing is the Tire Industry Association’s senior vice president of training.