A Century Old – But Just Getting Started: Max Finkelstein Looks to the Next 100 Years

Before there was a tire business, there was a junk business, and Harry Finkelstein was known as a “junk man.” He tore apart used radiators and refrigerators and sold the metal to scrappers in New York.

On Dec. 23, 1912, Harry Finkelstein died when a horse leading his wagon was spooked by a whistle and Harry was thrown from the wagon. His oldest son, Max, who was onboard, too, was injured, but survived. At age 15, Max Finkelstein became the man of the house, and his family’s business.

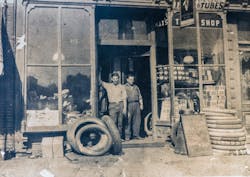

During World War I, there was great demand for metal, which was recycled into ammunition and bombs. But after the war ended, the junk business wasn’t so profitable. So in 1919, Max Finkelstein placed a couple of used tires in front of the store and sold them. And that was the start of the Finkelstein family’s tire business.

A century later, Max Finkelstein Inc. still claims that same street corner in the Astoria neighborhood of Queens, and the fourth generation of Finkelsteins is at work in one of the country’s largest wholesale tire distribution companies.Starting with hustle and service

Max and his younger brother, Irving, hustled to make a business out of those tires. “When they got a customer — a live one — the first thing they did was jack up the car so (the customer) couldn’t take it out,” says Irving’s oldest son, Harold. The act may have appeared as their urgent response to a customer’s need, but it really was a distraction from a tire inventory problem — because there was no inventory.

Max would leave Irving to attend to the store and the customer, and he’d jump on the train — which continues to rumble past the store — to go into Manhattan and buy the tires. He’d carry them underneath his arms, hop on the train and return to the store. “And that’s how they started.”

The turn to wholesaling was just as simple. “Max couldn’t stand letting a bargain go by,” Harold says. If the price of buying 20 tires was better than buying a single tire, he’d buy 20. “But he had no customers, so he’d go back out and try to find other dealers who could use the tires. And that’s how they got into the wholesale business.”

As adults, Harold and his brother, Jerry, officially joined the business in 1955 and 1957, respectively, though they had spent their childhoods growing up alongside their dad and uncle at work. Two more generations have followed Harold and Jerry into the family business.

The Goodyear connection

Each generation of the Finkelstein family has associated itself with Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. The connection goes back to 1923.

Brian Finkelstein, vice president of sales and a member of the fourth generation, says the company’s 96 years with Goodyear is more than a number.

“It means we’re a team and it’s a remarkable legacy that three generations can celebrate this year. They’ll always be our main supplier and partner.”

“Goodyear will always be our flagship brand,” says Ira Silver, CEO and president of Max Finkelstein. “When people hear the name Max Finkelstein, they immediately associate us with Goodyear.”

Goodyear recognizes the unique relationship, too. In the foreword to a history book published this year detailing the Max Finkelstein story, Rich Kramer, chairman, CEO and president of Goodyear, wrote that the dealership “has been an integral part of Goodyear’s legacy for almost the entirety of our history.”

That’s not an overstatement. In 1986, when Goodyear was a takeover target by Sir James Goldsmith, Harold and Jerry Finkelstein helped lead an army of Goodyear dealers in supporting the tire maker. They helped raise $80,000 to place a full-page ad in the Wall Street Journal with this giant-sized headline: “Goodyear is being torn apart by a foreign invader.”In a thank you letter to the Finkelsteins, Goodyear’s president at the time, Tom Barrett, wrote that the advertisement “delivered one of the bloody blows” that convinced Goldsmith to end the hostile takeover.

In the mid-1950s, Max Finkelstein dropped all its other brands to become a Goodyear-only tire dealer. Harold remembers, “Everybody said I was stupid.”

But it worked. “We grew very well with Goodyear,” he says.

It took three decades for Max Finkelstein to diversify and add other brands to its mix, and it wasn’t until 2018 that the tire distributor added another Tier 1 brand, Bridgestone, to its offerings.

That’s just one sign the company isn’t afraid to adapt to the current market.

Seven other brands were added between 2012 and 2018: Kumho, Aeolus, Kenda, Presa, Americus, Falken and Firestone. And in 2019, the company stocks nearly two dozen brands across the consumer, truck, off-the-road, specialty, trailer and lawn and garden categories.

Adding brands has come as Max Finkelstein has expanded its footprint with more warehouses, employees, routes and inventory.

In 2008 the company had five distribution centers and recorded sales of $100 million. Since then, the company has quadrupled in size.

“We will continue to work as a team and preserve what we have built over the past 100 years,” says Silver.

More than preserving, the company is looking for more opportunities to grow. In September, the tire wholesaler opened a new warehouse near Pittsburgh, Pa., to push into new states and markets. It’s the company’s westernmost location, and it’s already serving customers in western Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Ohio.

It’s proof that Max Finkelstein remains hungry. The company knows complacency isn’t an option in an industry where profit is driven by growth. But the company also isn’t hung up on adding a specific number of sites each year. It all depends on market conditions and potential.

Some markets have been especially affected by industry disruption and consolidation, and leaders of Max Finkelstein see an opening for their strategy. So they take the risk, and believe their consistent game plan and execution will help them succeed. ■

Special thanks to Max Finkelstein for sharing its archives, and to Melanie Paticoff Grossman, author of “Max Finkelstein Inc. A Centennial Story.”

Work-life balance is an old issue

Finkelstein developed win-win solution for employees, management

It was 1990. Jerry Finkelstein and his brother, Harold Finkelstein, were both working six days a week, and Jerry knew they needed to cut back. But their one retail store, which still stands, was open on Saturdays.

Jerry said he wasn’t going to work Saturdays anymore. Harold balked, and said they had to be there to oversee their employees. Jerry said they had managers who could do the job, and that would give the two of them a better quality of life.

Harold didn’t like the idea. A few days, later Jerry countered with another idea. “I think we should close Saturdays.” His brother was appalled and argued that the employees counted on those work hours.

More time passed. Jerry offered another solution. What if they opened a half-hour earlier and closed a half-hour later on weekdays? The hourly employees would work more hours, and they’d also have Saturdays off.

“That will help us hire people, too,” he said. “We are missing out on hiring the most qualified young people. Kids coming out of college don’t want to work six days a week anymore.”

Harold agreed to give it a try. They closed on Saturdays. Business grew by 30% that year.

Years later, Jerry told his brother he was going to stop working on Fridays. Harold shrugged. Months went by, and then Harold said he was going to do the same. What inspired the change? His wife, Marilyn, wanted to know why he was working while his brother Jerry was home with his wife, Estelle, on Fridays.

“That’s how it went with my brother and me. We complemented each other and made decisions together. In this instance, together we figured out a way to give our associates the hours they needed, while getting more time for ourselves to spend with family and enjoy hobbies. By delegating greater responsibility to our associates, we were able to build a team of competent employees and managers that we were able to rely on when we weren’t personally in the office.”

By the Numbers

Max Finkelstein Inc. is focused on responsible, profitable growth over the long haul. A few figures help to tell the story.

* 1 million tires in stock

* 100,000 square feet (average size of a distribution center)

* 80,000 tires (average number of consumer and commercial tires in a distribution center)

* 500 employees

* 250 trucks

* 1 retail store

About the Author

Joy Kopcha

Managing Editor

Joy Kopcha joined Modern Tire Dealer and Auto Service Professional as senior editor in 2014 after working as a newspaper reporter for a dozen years in Kansas, Indiana and Pennsylvania. She was named managing editor of MTD and ASP in 2022, and took on that same role with Motor Age in 2024.

She is an award-winning journalist, including in 2023 when she was named a Jesse H. Neal Awards Finalist.

Don't miss any of her articles. Sign up for MTD's newsletters.